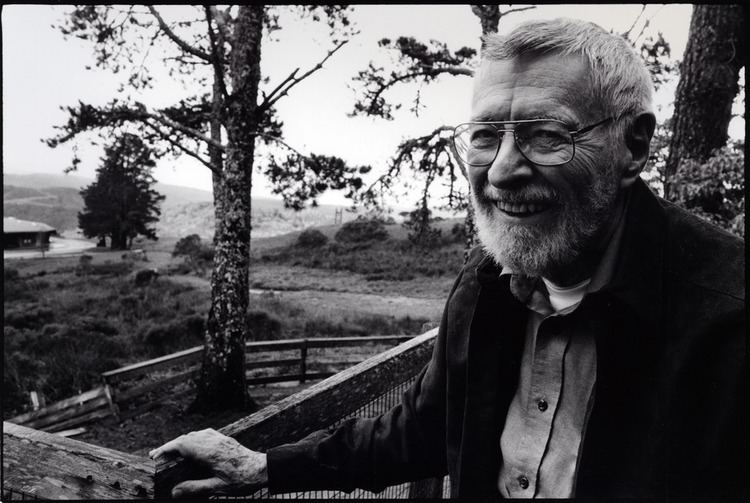

We note today, sadly, of the passing of composer Ben Johnston. A unique voice in the American composition landscape, Mr. Johnston created a singular body of work that was primarily involved with a focus on intonation, and specifically just intonation. Much of the inspiration from this came from an early period in his life, which he describes thus (from “A Conversation with Ben Johnston”):

In 1949 and ‘50 I went out to California and worked for six months with Harry Partch. It was going to be a whole year, but he got ill and closed up his studio. So I went to Mills and studied with Milhaud for the balance of the year. Then I got a job at the University of Illinois, and within a few years we brought Partch there and did some of his large works. I was involved very heavily in the business end of the production of The Bewitched, but not in subsequent productions. That was atypical of me, and they were sponsored not by music but by theater, and later by the student groups. He was around in this area, including Chicago. He was living in Evanston for a while and did a film with Madeline Tourtelot during the late fifties or early sixties, but he went back to California where he stayed the rest of his life. This was a fruitful period for him, being in this part of the country. I don’t think he liked it terribly well; he likes the west, but it was fascinating to have him around. So all during that period I was exposed to something. The reason I went to study with him was because a musicologist told me — after we had a discussion about how music theory wasn’t based on acoustics, and I was objecting that it ought to be and that it wasn’t — he said, “I have a book you should read,” and gave me Genesis of a Music. So I read it, and then I wrote to the publisher and they forwarded the letter — which they won’t always do, but it was a friend of his. So she forwarded the letter to him and we corresponded for a while. I realized rather quickly that I couldn’t get very far without really being there and hearing what was going on; that if I tried to do it myself, I would probably come to grief, and I think I would have. It’s just too difficult and too expensive, and too a lot of things. So I went out there, and that was the beginning of my active interest in that kind of thing.

His relationship with Partch was complicated and not always smooth. There were difficult issues almost from the beginning. In spite of that, or perhaps because of it, Mr. Johnston took those early influences and went on to create a body of music that has no real parallel. In the sense that he carved his very own path over a long and dedicated musical journey, there could be no better tribute to his work with Partch than striking out on his own. We hope he rests in amazing grace.